As we enter into the Northern Hemisphere autumn, and I get out of holiday mode, a starting hypothesis for the book is emerging. This comes from a combination of reading lots around the subject of randomness, spending a few weeks in a country and culture where randomness appears to take a different role to what I have come to expect, and also simply from not thinking about the book too much when I was away.

The hypothesis goes like this:

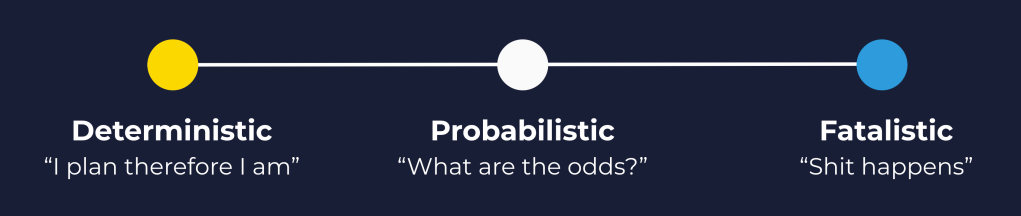

In our culture, our experience of randomness by and large is reactive, and sits somewhere on a spectrum where at one end we pretend we can completely control the world around us and all of our actions drive outcomes (“Deterministic”) and at the other end that we a totally at the mercy of external events and there’s nothing that we can do about it (“Fatalistic”).

As with any continuum like this, life mostly happens in the middle, where a “Probabilistic” approach assesses the odds of things happening and we create contingencies and mitigations on the basis of that assessment.

This is, though, flawed because of our innate inability to successfully assess the likelihood of things. Witness the way in which many people are terrified of flying, yet the most dangerous part of an air journey is getting to and from airports.

Our reactive approaches to random things may or may not work well for us. The better we get at being able to assess probabilities, the better we become at managing our lives? That will be interesting to explore.

I’m also curious, though, as to whether there are completely alternative strategies to this continuum that, rather that seeing randomness as an externality to be reactive to, we can take randomness as a tool to exploit. I’m reminded of my conversation with Chris Thorpe about T-Cells. Are there examples of human behaviours where randomness is a strategy, not merely a complication or opportunity?

Love to hear what you make of this…

Leave a comment